Richard Nixon's Greatest

Cover-Up:

His Ties to the Assassination of President

Kennedy

by Don Fulsom

Seared into the memories of all Americans who lived through the assassination of President John F. Kennedy is exactly where they were on November 22, 1963. Yet private citizen Richard Nixon, who — believe it or not — was in Dallas, could not recall this fact in a post-assassination interview with the FBI.The interview dealt with an apparently false claim by Marina Oswald that her husband —alleged Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald — had targeted Nixon for death during an earlier trip to Dallas. A Feb. 28, 1964 FBI report on the interview said Nixon "advised that the only time he was in Dallas, Texas, during 1963 was two days prior to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy."

While Nixon eventually came clean regarding his whereabouts on that fateful day, he seemed touchy whenever the matter was raised. For example, in a 1992 interview with CNN's Larry King, Nixon interjected he was in Dallas "In the morning!" when King cited the presumed geographical coincidence. Nixon left Dallas on a flight to New York several hours before Kennedy's noontime arrival at Love Field.

Not only did Nixon misremember where he was on November 22nd, he made at least two conflicting statements about how he first learned his archrival had been shot. In a 1964 Reader's Digest article, he recalled hailing a cab after his Dallas-New York flight: "We were waiting for a light to change when a man ran over from the street corner and said that the President had just been shot in Dallas." In November of 1973, however, Nixon said in Esquire that his cabbie "missed a turn somewhere and we were off the highway...a woman came out of her house screaming and crying. I rolled down the cab window to ask what the matter was and when she saw my face she turned even paler. She told me that John Kennedy had just been shot in Dallas."

In yet another curious twist, a November 22nd wire service photo of Nixon indicates he might even have learned of the shooting before his cab ride. In the photo, a glum-looking Nixon, hat in lap, is sitting in what appears to be an airline terminal. The caption on the United Press International photo reads: "Shocked Richard Nixon, the former vice president who lost the presidential election to President Kennedy in 1960, is shown Friday after he arrived at Idlewild Airport in New York following a flight from Dallas, Tex., where he had been on a business trip."

In the 1992 King interview, Nixon maintained he'd never had any interest in digging into the JFK assassination: "I don't see a useful purpose in getting into that and I don't think it's frankly useful for the Kennedy family to constantly raise that up again."

Nixon's professed disinterest doesn't ring true, however, for it came from one of our snoopiest chief executives — a politician who just relished investigations, spying, secrets, and conspiracies. As Nixon aide John Ehrlichman once observed: "He was a conspiracy buff. He liked intrigue, and he liked secret maneuverings of the FBI, and he liked to hear about what the CIA did, and so on. He just couldn't leave that stuff alone."

As for Nixon's stated compassion for the Kennedys, let's not forget that he deeply despised them. So much so that, as president, he ordered chief White House spy E. Howard Hunt to forge diplomatic cables to make it look like President Kennedy ordered the murder of South Vietnamese leader Ngo Dinh Diem. He sent another spy, Anthony Ulasewicz, to Chappaquiddick, Mass., to investigate the 1969 crash of a car driven by Edward Kennedy that killed the senator's female companion. He placed Sen. Kennedy under a 24-hour-a-day Secret Service surveillance in an effort, in Nixon's phrase, "to catch him in the sack with one of his babes." And Nixon pressed aides to plant a false story in the press linking Sen. Kennedy to the 1972 assassination attempt against Alabama Gov. George Wallace.

What did Nixon do in Dallas? He arrived on Nov. 20 to attend a board meeting of the Pepsi Cola Company, one of his law clients. Dallas reporter Jim Marrs says Nixon and actress Joan Crawford, a Pepsi heiress, "made comments to the effect that they, unlike the president, didn't need Secret Service protection, and they intimated the nation was upset with Kennedy's policies. It has been suggested that this taunting may have been responsible for Kennedy's critical decision not to order the Plexiglas top placed on his limousine on Nov. 22."

When adviser Stephen Hess saw Nixon that same afternoon at the former vice president's New York apartment, he said Nixon was "pretty shook up." Hess later portrayed his boss to political reporter Jules Witcover as unusually defensive about his pre-assassination comments in Dallas: "He had the morning paper, which he made a great effort to show me, reporting he had held a press conference in Dallas and made a statement that you can disagree with a person without being discourteous to him or interfering with him. He tried to make the point that he had tried to prevent it … It was his way of saying, ‘Look, I didn't fuel this thing.'"

What Nixon apparently failed to tell Hess was that the major story from his meeting with reporters in Dallas was certain to fuel the anger of some Texans toward Kennedy. The headline in the Dallas Morning News on November 22 said: "Nixon Predicts JFK May Drop Johnson." Vice President Lyndon Johnson was, of course, a Texan.

On the morning after the assassination, Nixon convened a meeting of Republican leaders at his New York apartment. Those assembled were "already assessing how this event would affect or recreate the possibilities of Nixon running for president," according to Hess.

Boasting that he was the mastermind of a Mob/CIA plot to kill President Kennedy, Chicago godfather Sam Giancana told relatives he was in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963 to supervise that plot. Giancana claimed that both "Richard Nixon and Lyndon Johnson knew about the whole damn thing"— adding that he had met with both future presidents in Dallas "immediately prior to the assassination."

Giancana's half-bother Chuck and nephew Sam claimed in their 1992 book Double Cross that the Mafia don had a long, warm, and mutually rewarding relationship with Nixon that dated back to the 1940s. In those times, Giancana was helping Chicago Syndicate boss Anthony Accardo consolidate the city's rackets and gambling operations, and Nixon was a freshman congressman from California. In recounting for his relatives a big favor the congressman did for Giancana back then, the gangster established a direct link between Nixon and a Chicago hoodlum who later moved to Texas and went on to shoot Lee Harvey Oswald: "Nixon's done me some favors, all right, got us some highway contracts, worked with the unions and overseas. And we've helped him and his CIA buddies out, too. Shit, he even helped my guy in Texas, (Jack) Ruby, get out of testifying in front of Congress back in forty-seven … By sayin' Ruby worked for him."

A 1947 memo, found in 1975 by a scholar going through a pile of recently released FBI documents, supports Giancana's contention. In the memo, addressed to a congressional committee investigating organized crime, an FBI assistant states: "It is my sworn testimony that one Jack Rubenstein of Chicago ... is performing information functions for the staff of Congressman Richard Nixon, Republican of California. It is requested Rubenstein not be called for open testimony in the aforementioned hearings." (Later in 1947, Rubenstein moved to Dallas and shortened his last name.) The FBI subsequently called the memo a fake, but the reference service Facts on File considers it authentic.

Undercover work for the young Congressman Nixon would have been in keeping with Ruby's history as a police tipster and government informant. In 1950, Ruby gave closed-door testimony to Estes Kefauver's special Senate committee investigating organized crime. Committee staffer Luis Kutner later described Ruby as "a syndicate lieutenant who had been sent to Dallas to serve as a liaison for Chicago mobsters." In exchange for Ruby's testimony, the FBI is said to have eased up on its probe of organized crime in Dallas. In 1959, Ruby became an informant for the FBI.

Ruby's old Chicago boss, Giancana, was murdered in his home in Oak Park, Ill., in 1975 — shortly before he was to have appeared before a Senate committee investigating assassinations. Seven .22-caliber bullets were blasted into his mouth and neck, Mob symbolism for "talks too much."

Giancana had never been adept at keeping secrets. When Mob/CIA hit teams were planning to assassinate Cuban leader Fidel Castro in 1960 — an operation reportedly overseen by Vice President Richard Nixon—Giancana's loose lips allowed FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to discover the plans.

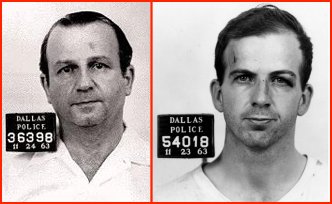

Lee Harvey Oswald was at his Dallas job as an order-filler at the Texas School Book Depository on Nov. 22. Shortly after shots rang out in Dealey Plaza, Oswald fled the crime scene. Later that afternoon, a policeman trying to arrest Oswald was shot to death. After a struggle with the armed Oswald in a movie theater, police apprehended him and charged him with the murders of both President Kennedy and the policeman.

In 1964, a presidential commission headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren concluded that Oswald — firing a rifle from a sniper's nest on the sixth floor of the depository — was Kennedy's sole assassin. The commission portrayed Oswald as a ''discontented'' loner whose "avowed commitment to Marxism and Communism" might have contributed to his deed. But the Warren Commission had not looked carefully at the alleged assassin's ties to the Syndicate. In New Orleans — where Oswald spent significant portions of his life — Oswald's uncle and substitute father was Charles "Dutz" Murret, an important bookie in godfather Carlos Marcello's gambling apparatus. Oswald's mother, Marguerite, dated members of Marcello's gang. Oswald friend David Ferrie worked for Marcello; had alleged ties to the CIA; and, in 1967, was named by New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison as a key JFK assassination plotter.

The exact route of the presidential motorcade was announced far in advance of the event — a practice the Secret Service halted in the wake of the JFK assassination.

Just two days before President Kennedy's murder, suspicious activity caught the eyes of two Dallas policemen on routine patrol in Dealey Plaza. The officers observed several men with rifles standing behind the picket fence on the plaza's grassy knoll. The riflemen were participating in mock target practice —aiming their guns over the fence in the direction of the street. By the time the patrolmen reached the area, however, the unidentified men had vanished.

Realizing the significance of this information in the immediate aftermath of the assassination, Dallas police forwarded it to the FBI. But an FBI report on the incident, dated Nov. 26 1963, apparently was not turned over to the Warren Commission. This report — clearly pointing to a conspiracy — was finally made public in 1978 in response to a Freedom of Information request.

In 1979, a House committee differed with the commission's finding that Oswald acted alone. After a two-year study, the panel indicated there were at least two shooters, declared that Kennedy "was probably assassinated as a result of a conspiracy," and it fingered the Mafia as having the "motive, means, and opportunity." Two top committee staffers — Robert Blakey and Richard Billings — later wrote of their conviction that "Oswald was acting in behalf of members of the Mob, who wanted relief from the pressure of the Kennedy administration's war on crime led by Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy."

The two investigators flatly asserted that the president of the Mob-dominated Teamsters union, Jimmy Hoffa — along with Mob bosses Carlos Marcello, Santos Trafficante and Sam Giancana — planned and carried out the president's slaying. They said both Oswald and Ruby were Mafia-connected, and that Ruby silenced Oswald on orders from the Mob. In a recent book, former Mafia consigliere Bill Bonanno — the son of legendary New York godfather Joe Bonanno — also maintains that Hoffa, Marcello, Trafficante, and Giancana were involved in the JFK assassination.

In 2001, a scientific study supported the conclusion first propounded by the House committee in 1979: that sounds heard on police recordings from Dealey Plaza are consistent with a shot being fired from the famed grassy knoll — bolstering the panel's finding that Kennedy's murder probably resulted from a plot.

Jack Ruby was a busy man in Dallas on Nov. 22. Only hours before Kennedy's arrival, the debt-ridden striptease club operator met with Mafia paymaster Paul Jones. Shortly after Kennedy was shot, Ruby showed up at Parkland Hospital, where the president had been taken — though he later denied being there at that critical time. Minutes after Kennedy was pronounced dead, Ruby phoned Alex Gruber — an associate of one of Jimmy Hoffa's top officials, and a man with known connections to hoodlums who worked for racketeer Mickey Cohen. Ruby and Gruber had met 10 days earlier in Dallas. When he was arrested for killing Oswald two days later, Ruby had $2,000 on his person and authorities found $10,000 in his apartment.

On the evening of the 22nd, Ruby was hanging around on the same floor of the police station where Oswald was being questioned. He even attended the midnight police station press conference at which Oswald was trotted out briefly for the world to see. Ruby corrected the district attorney when he told reporters that Oswald belonged to the Free Cuba Committee, an anti-Castro outfit. Ruby pointed out that the D.A. had meant Fair Play for Cuba, a pro-Castro group.

Like Oswald, Ruby could well have been under the control of the Mob, especially of Marcello — whose territory extended to Dallas, and whose take from underworld activities in Louisiana alone at the time was put at $1 billion-a-year. Ruby had lifelong connections to the Mafia and was involved in slot machines and bookmaking operations under Marcello's command. In 1959, Ruby reportedly visited Mob boss Santos Trafficante in a Cuban prison. After Oswald's murder, Ruby's brother approached one of Jimmy Hoffa's lawyers to represent Ruby.

More than a dozen people claim to have seen Ruby and Oswald together during the four months prior to the Kennedy assassination. In 1994, Dallas reporters Ray and Mary La Fontaine claimed that, shortly after Oswald's arrest on Nov. 22, he told a cellmate that he and Ruby attended a meeting in a local hotel just days earlier.

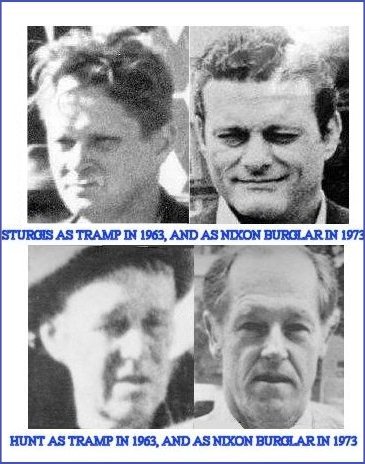

CIA agent E. Howard Hunt — Richard Nixon's top confederate in past and future undercover operations — may also have been in Dallas the day President Kennedy was killed. During a 1985 trial in Miami, CIA operative Morita Lorenz testified that, on Nov. 21, at a Dallas motel, she saw Hunt pay money to another agency operative — Hunt pal and future Watergate burglar Frank Sturgis. She maintained that, shortly after Hunt left, Jack Ruby showed up. Lorenz returned to her home in Miami that same night, but said Sturgis later told her what she had missed in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963: "We killed the president that day."

The testimony came in a suit brought by Hunt against the right-wing newsletter Spotlight for printing a 1978 article titled, "CIA to Admit Hunt Involvement in Kennedy Slaying." The jury ruled in favor of the newsletter.

At one time, Lorenz was Fidel Castro's girlfriend. In 1959, Hunt and Sturgis had recruited her into the CIA with the goal of killing the Cuban leader. At the trial, Lorenz identified Hunt as Sturgis's CIA paymaster. She said that, on Nov. 21, Hunt gave Sturgis an envelope of cash at the Dallas motel after she and Sturgis arrived there to take part in what she was told was a "confidential" operation.

In a deposition for the Miami trial, a reporter testified he had once seen an internal CIA memo, dated 1966, which said: "Some day we will have to explain Hunt's presence in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963." That reporter — Joseph Trento — had co-authored a 1978 article for the Wilmington News Journal headlined: "Was Hunt in Dallas the Day JFK Died?" His piece contained speculation by "some CIA sources" that "Hunt thought he was assigned by higher-ups to arrange the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald."

In 1975, a JFK assassination researcher in Texas received from an anonymous source a copy of a brief handwritten Nov. 8, 1963 note to a "Mr. Hunt" purportedly from Oswald. The writer asked for "information concerding [sic] my position. I am asking only for information. I am asking that we discuss the matter fully before any steps are taken by me or anyone else." Three handwriting experts found that the writing was that of Oswald. "Concerning" was also misspelled in a letter Oswald was known to have written in 1961.

That the note was meant for E. Howard Hunt makes sense. Oswald and Hunt once worked out of the same office building in New Orleans. On behalf of the CIA, Hunt had set up a dummy organization called "The Cuban Revolutionary Council" at 544 Camp Street — the same address Oswald put on pro-Castro leaflets he handed out. The same building also housed the detective agency of former FBI agent Guy Banister — who was associated with the CIA, the Mafia, Cuban exile leaders, and suspected JFK assassination plotter David Ferrie.

Ex-CIA agent Victor Marchetti has linked Hunt and Sturgis with Ferrie. Sturgis has claimed: that he knew Oswald; that documents existed at the CIA detailing the role of Ruby in the Kennedy killing; and that Oswald and Ruby once met in a hotel in New Orleans.

Though he was not in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963, Jimmy Hoffa played an important role in President Kennedy's murder, according to longtime Hoffa and Mob lawyer Frank Ragano, who detailed Hoffa's alleged involvement in 1994. Ragano said he carried a message from the Teamster's boss to a July 24, 1963 meeting with Marcello and Trafficante in New Orleans. The message: Hoffa "wants you to do a little favor for him. You won't believe this, but he wants you to kill John Kennedy. He wants you to get rid of the president right away."

Ragano said the facial expressions of the two Mob bosses "were icy. Their reticence was a signal that this was an uncomfortable subject, one they were unwilling to discuss." But Ragano said Trafficante, on his deathbed in 1987, confessed that he and Marcello did, indeed, follow through on Hoffa's "favor." Ragano quoted the ailing Mob chief as saying: "Who would have thought that someday he would be president and he would name his goddam brother attorney general? Goddam Bobby. I think Carlos fucked up in getting rid of Giovanni (John in Italian) — maybe it should have been Bobby."

Jimmy Hoffa hated John and Robert Kennedy as much as Richard Nixon did. Robert Kennedy had been trying to put Hoffa in jail since 1956, when he was staff counsel for a Senate probe into the Mob's influence on the labor movement. In 1960, Robert Kennedy said, "No group better fits the prototype of the old Al Capone syndicate than Jimmy Hoffa and some of his lieutenants."

In the 1960 presidential election, Hoffa and his two million-member union backed Vice President Nixon against Sen. John Kennedy. Edward Partin, a Louisiana Teamster official and later government informant, eventually revealed that Hoffa met with Marcello to secretly fund the Nixon campaign — saying, "I was right there, listening to the conversation. Marcello had a suitcase filled with $500,000 cash which was going to Nixon ... (Another half-million dollar contribution) was coming from Mob boys in New Jersey and Florida." The Hoffa-Marcello meeting took place in New Orleans on Sept. 26, 1960, and has been verified by William Sullivan, a former top FBI official.

Nixon lost the 1960 election, and Hoffa — thanks to Attorney General Robert Kennedy — soon wound up in prison for jury tampering and looting the union's pension funds of almost $2 million. But the Nixon-Hoffa connection was strong enough to last at least until Dec. 23, 1971—when, as president, Nixon gave Hoffa an executive grant of clemency, allowing Hoffa to serve just five years of a 13-year prison term.

Nixon apparently sprung Hoffa in exchange for a big underworld payoff.

A recently released FBI memo backs up an earlier claim by an FBI informant that James P. ("Junior") Hoffa — current head of the Teamsters — and racketeer Allen Dorfman delivered $300,000 in a black valise to a Nixon bagman at a Washington hotel to secure the elder Hoffa's release from the pen.

Breaking from clemency custom, Nixon did not consult the judge who had sentenced Hoffa. Nor did he pay any mind to the U.S. Parole Board — which had been warned by the Justice Department that Hoffa was Mob-connected. At the time, The New York Times called the clemency a "pivotal element in the strange love affair between the (Nixon) administration and the two-million-member truck union…" Former Mafia bigwig Joe Bonanno recently described Nixon's clemency for Hoffa as "a gesture — if ever there was one, of the national power (the Mob) once enjoyed."

President Nixon did put one restriction on Hoffa's freedom: He could never again, directly or indirectly, manage any union. The restriction — a favor to Hoffa's successor, Frank Fitzsimmons — was reputedly bought by a $500,000 contribution to the Nixon campaign by New Jersey Teamster leader Anthony Provenzano.

In July 1975, Hoffa vanished in a Detroit suburb and his body has never been found. Many federal and local investigators believe he was shot to death after being lured to a meeting with Provenzano. They speculate that Hoffa's body was taken away by truck, stuffed into a fifty-gallon drum — then crushed and smelted.

Newly released FBI documents show that, in 1978, federal investigators sought to force Nixon and Fitzsimmons to testify about events surrounding Hoffa's disappearance. The investigators had concluded that such testimony offered the last, best chance of solving the Hoffa mystery. But they accused top Justice Department officials of derailing their efforts to call the ex-president and the Teamster boss before a Detroit grand jury.

The records also reveal that FBI agents suspected the Nixon White House of soliciting $1 million from the Teamsters to pay hush money to the Watergate burglars. In fact, in early 1973 — when the Watergate cover-up was coming apart at the seams — aide John Dean told the president that $1 million might be needed to keep the burglary team silent. Nixon responded, "We could get that … you could get a million dollars. You could get it in cash, I know where it could be gotten." When Dean observed that money laundering "is the type of thing Mafia people can do," Nixon calmly answered: "Maybe it takes a gang to do that."

In August 1974, Nixon became the first president forced to quit the office. He did so as Congress prepared to impeach and expel him for a wide range of illegal activities and abuses of constitutional power he directed or concealed during the Watergate scandal. Forty Nixon administration officials were indicted or jailed. The president was named by a grand jury as an unindicted co-conspirator. In what smacked of a sweetheart deal, one month after he stepped down, Nixon's handpicked successor — President Gerald Ford — granted him a complete pardon for all the presidential crimes he might have committed.

After spending more than a year brooding in self-exile at his walled estate in San Clemente, Calif., the very first post-resignation invitation Nixon accepted was from his Teamsters buddies. On Oct. 9, 1975, he played golf at a Mob-owned California resort with Fitzsimmons and other top Teamsters. Among those who attended a post-golf game party for Nixon were Anthony Provenzano, Allen Dorfman, and the union's executive secretary, Murray ("Dusty") Miller.

A convicted Mafia killer, Provenzano went on to become a prime suspect in Hoffa's disappearance. In the two months before President Kennedy's assassination, Jack Ruby was in telephone contact with Murray Miller, and with Barney Baker — who was once described by Robert Kennedy as "Hoffa's ambassador of violence." Ruby was also in touch with key figures from the Marcello, Trafficante, and Giancana crime families.

Documents that came to light in 2007 show that, shortly after the president's murder, Atty. Gen. Robert Kennedy's right-hand man Walter Sheridan – dispatched by RFK on a secret investigative mission to Dallas – quickly reported back that Jimmy Hoffa associate Allen Dorfman had paid off Jack Ruby in Chicago. A witness to that payoff – reportedly of $7,000 in 100 dollar bills stuffed into a manila envelope – says it occurred on the weekend of Oct. 27th 1963.

James P. "Junior" Hoffa has said, "I think my dad knew Jack Ruby, but from what I understand, he (Ruby) was the kind of guy everybody knew. So what?" JFK assassination authority Anthony Summers reasons, however, that — given Hoffa's record of threats against the lives of both John and Robert Kennedy — "the potential significance of such a connection is immense."

Mob experts connect Richard Nixon to Carlos Marcello — and to Jimmy Hoffa — through Nixon's earliest campaign manager and longest-serving adviser, Murray Chotiner. And they tie Nixon to Santos Trafficante through Nixon's best friend, Florida banker Bebe Rebozo. Mickey Cohen — one of the most notorious mobsters in Los Angeles — admitted rounding up underworld money for two early Nixon campaigns.

Charles Colson — Nixon's presidential emissary to the Teamsters — once raised the theory that Mafia bosses "owned" Rebozo and had gotten "their hooks into Nixon early." By the 1960s, FBI agents keeping tabs on the Mob had identified Rebozo as a "non-member associate of organized crime figures," it is now known. An off-the-books military probe conducted in the waning days of the Nixon presidency found "strong indications of a history of Nixon connections with money from organized crime," the chief investigator later revealed.

In an unpublicized presidential move, Nixon ordered the Justice Department to stop using the words "Mafia" and "Cosa Nostra" to describe the multi-billion dollar national crime syndicate. The president was roundly applauded when he boasted about his order at a private 1971 Oval Office meeting with some 40 members of the Supreme Council of the Sons of Italy. The group's Supreme Venerable, Americo Cortese, thanked Nixon for his moral leadership — declaring, "You are our terrestrial god."

The Nixon administration intervened on the side of Mafia figures in at least 20 trials. And it denied an FBI request to continue an electronic surveillance operation that was starting to penetrate Mob/Teamsters connections.

During the Nixon years, pressure from Washington eased off on Sam Giancana. And long-standing deportation proceedings against CIA-connected mobster Johnny Roselli were dropped. Without going into specifics, government lawyers explained in court that Roselli had performed "valuable services to the national security." A Giancana henchman, Roselli was an important contact man in the Mob/CIA assassination plots against Cuban leader Fidel Castro.

Roselli and Jack Ruby are reported to have met in hotels in Miami during the months before the JFK assassination. Years later, Roselli told columnist Jack Anderson: "When Oswald was picked up, the underworld conspirators feared he would crack and disclose information that might lead to them. This almost certainly would have brought a massive U.S. crackdown on the Mafia. So Jack Ruby was ordered to eliminate Oswald . . ."

In the mid-‘70s, as congressional committees probed the Mob and the CIA, Roselli was dismembered, squeezed into an oil drum, and tossed off the Florida coast; Giancana was gunned down in his kitchen; and Jimmy Hoffa disappeared.

Back in the Eisenhower years, Vice President Richard Nixon and CIA agent E. Howard Hunt were principal secret planners of the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba that failed so miserably when it was later launched by President Kennedy. Some historians are convinced Nixon was a prime mover in an associated — and also ill-fated — plot to assassinate Fidel Castro. For example, onetime Nixon aide Roger Morris says Nixon "had been an avid supporter of the Eisenhower administration's covert operations to overthrow Castro, including the alliance with organized crime to assassinate the Cuban leader." For his part, Hunt has readily admitted his role in efforts to murder Castro.

For the "executive action" mission, potential assassins were recruited from Mafia ranks, so that if any of their activities were disclosed, organized crime could be blamed.

Nixon confidant Robert Maheu fronted for the CIA on the Mob plots. A high-end private eye (and ex-FBI undercover operative) who functioned in the shadowy realm between U.S. intelligence services and the national criminal syndicate, Maheu had performed previous "dirty tricks" for both Nixon and Giancana. Hoffa had also been a client of Maheu, who would eventually become the top aide to Mob-and CIA-connected billionaire and Nixon financial angel Howard Hughes.

The hit on Castro was to have been carried out at the same time as the secret Nixon-Hunt plan for the invasion by CIA-trained exiles. The invasion was a military debacle when later ordered by President Kennedy — who publicly accepted full responsibility for the April 17, 1961 landing in which 1,500 exiles were quickly overwhelmed by some 20,000 Cuban troops. Convinced, however, that the CIA set him up, Kennedy fired CIA chief Allen Dulles — an old Nixon friend — and swore he'd dismantle the agency.

Nixon, Hunt, and many CIA and Cuban exile leaders pinned almost complete blame for the military catastrophe on Kennedy for not providing adequate air cover. At the time, Nixon told a reporter it was "near criminal" for Kennedy to have canceled the air cover. Privately, he must have been just as upset that Castro had not been bumped off. In one of his many books, Hunt later accused the president of "a failure of nerves."

Nixon's secret Mafia buddies, already enraged by Kennedy's anti-crime crusade in this country, were furious that their lucrative gambling casinos — shuttered by Castro — would not be returning to Cuba.

In the immediate aftermath of his brother's murder, Atty. Gen. Robert Kennedy suspected the Mafia – as well as the CIA and the Cuban exiles. And he soon became consumed by a desire to track down, expose and punish the plotters during what he hoped would be his own time in the White House, according to David Talbot in Brothers: The Hidden History of the Kennedy Years, published in 2007. Talbot says RFK's quest began on the very afternoon of the assassination in Dallas:

(Bobby) frantically worked the phones at Hickory Hill – his Civil War-era mansion in McLean, Va. – and summoned aides and government officials to his home. Lit up with the clarity of shock, the electricity of adrenaline, Bobby Kennedy constructed the outlines of the crime that day – a crime, he immediately concluded, that went far beyond Lee Harvey Oswald, the 24-year-old ex-Marine arrested shortly after the assassination. Robert Kennedy was America's first assassination conspiracy theorist.

Through fresh interviews, newly released documents and gripping words, Talbot makes a compelling case that Bobby's reluctance to publicly discuss his brother's death was a ruse. To family members, however, Bobby confided, "JFK had been killed by a powerful plot that grew out of one of the government's secret anti-Castro operations. There was nothing they could do at that point, Bobby added, since they were facing a formidable enemy and they no longer controlled the government."

E. Howard Hunt, of course, went on to become President Nixon's chief dirty trickster and secret intelligence operative. In 1972, five Hunt-recruited former CIA men — all veterans of the Bay of Pigs invasion planning — were caught by police while burglarizing Democratic headquarters at the Watergate office building in Washington. Fearing that Hunt's role would soon be learned — and the burglary traced back to the White House —Nixon immediately set out to blackmail g an FBI investigation of the break-in. He had his chief of staff, Bob Haldeman, tell CIA Director Richard Helms that Hunt, if apprehended, might spill the beans about a major CIA secret. On one of the original Watergate tapes, the president rehearsed Haldeman on exactly what to tell the intelligence chief: "Hunt knows too damned much ... If this gets out that this is all involved ... it would make the CIA look bad, it's going to make Hunt look bad, and it's likely to blow the whole Bay of Pigs thing ... which we think would be very unfortunate for both the CIA and the country ... and for American foreign policy."

In a generally overlooked revelation in a post-Watergate book, Haldeman said: "It seems that in all those Nixon references to the Bay of Pigs, he was actually referring to the Kennedy assassination. (Interestingly, an investigation of the Kennedy assassination was a project I suggested when I first entered the White House. Now I felt we would be in a position to get all the facts. But Nixon turned me down.)" Haldeman added that the CIA pulled off a "fantastic cover-up" that "literally erased any connection between the Kennedy assassination and the CIA."

On a White House tape made public in the 1990s, Haldeman fingered Nixon as the source of his information that the CIA had reason to fear Hunt's possible disclosure of "Bay of Pigs" secrets. The newest Nixon tapes are studded with deletions — segments deemed by government censors as too sensitive for public scrutiny. "National Security" is cited. Not surprisingly, such deletions often occur during discussions involving the Bay of Pigs, E. Howard Hunt, and John F. Kennedy.

One of the most tantalizing nuggets about Nixon's possible inside knowledge of JFK assassination secrets was buried on a White House tape until 2002. On the tape, recorded in May of 1972, the president confided to two top aides that the Warren Commission pulled off "the greatest hoax that has ever been perpetuated." Unfortunately, he did not elaborate. But the context in which Nixon raised the matter shows just how low he could stoop in efforts to assassinate the character of his political adversaries.

The Republican president made the "hoax" observation in the immediate aftermath of the assassination attempt against White House hopeful George Wallace, a longtime Democratic governor of Alabama. The attempt left Wallace paralyzed below the waist. Nixon blurted out his comments about the falsity of the Warren findings in the middle of a conversation in which he repeatedly directed two of his most ruthless aides, Bob Haldeman and Chuck Colson, to carry out a monumental dirty trick. He urged them to plant a false news story linking the would-be Wallace assassin — Arthur Bremer — to two other Democrats, Sen. Edward Kennedy and Sen. George McGovern —possible Nixon opponents in that year's fall elections. "Screw the record," the president orders on at one point. "Just say he was a supporter of that nut (it isn't clear which of the two senators he is referring to). And put it out. Just say we have an authenticated report."

As well as helping to perpetuate the Kennedy assassination "hoax" by turning down Haldeman's proposal for a new JFK probe, Nixon had a major hand in perpetrating it. In November of 1964, on the eve of the official release of the Warren Report, private citizen Nixon went public in support of the panel's coming findings. In a piece for Reader's Digest, he portrayed Oswald as the sole assassin. And Nixon implied that Castro — "a hero in the warped mind" of Oswald — was the real culprit.

Why did Nixon declare his belief in Oswald's guilt just before publication of the commission's report? Was he acting in league with his old buddies at the CIA and the FBI — as well as in the best interests of the Mob — to give advance support to what they knew would be the report's lone-killer conclusion? And why did Nixon stress Castro's alleged hold over Oswald's thinking? Was he trying to ramp up enthusiasm for further efforts to topple the Cuban leader?

In an apparent slip of the lip that got little attention at the time, a Watergate-stressed President Nixon himself suggested there was a conspiracy behind the JFK assassination. In the summer of 1973, the president publicly raised the assassination issue to divert attention from recent disclosures of a widespread government wiretapping operation. He claimed that Robert Kennedy, as attorney general, had authorized a larger number of wiretaps than his own administration. "But I don't criticize it," he declared, adding, "if he had ten more and — as a result of wiretaps — had been able to discover the Oswald Plan, it would have been worth it."

Whoops! The president apparently didn't realize his reference to "the Oswald Plan" didn't square with the government's official lone-killer finding. For if Lee Harvey Oswald had been solely responsible for the assassination, then there would not have been anyone for Oswald to conspire with about his "plan" — on a bugged telephone, or otherwise. Was Nixon inadvertently revealing his knowledge that Mob leaders (Robert Kennedy's main wiretap targets) had a role in President Kennedy's slaying? Was such a belief based on information acquired as a result of Nixon's own solid ties to organized crime and the Mafia-infested Teamsters union?

In the late 1970s, the House assassinations committee studied FBI electronic surveillance of the Mob over several months just before and after the JFK assassination. It found what Mob expert Ron Goldfarb has described as "expressions of outrage and betrayal and comments about ‘wacking out Kennedy.'"

That's because the Syndicate's tentacles had briefly entangled John F. Kennedy too. In crucial ways, the Mafia had helped the Massachusetts senator gain the presidency in 1960 — in exchange for a go-easy attitude toward the Mob by the future Kennedy administration. Instead of keeping his end of the bargain, however, President Kennedy started waging war on the Mafia — and the godfathers went crazy with rage.

Of all the illegal activities undertaken by President Nixon's secret agents E. Howard Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy, one stands out as particularly sordid — the planned assassination of newspaper columnist Jack Anderson, Nixon's arch foe in the media. Nixon-era stories by Anderson about mobster Johnny Roselli (the Mafia's liaison with the CIA) and various Mob/CIA plots infuriated the president and led to White House discussions about the columnist's murder.

The plot against Anderson came to light in 1975 when The Washington Post reported that — "according to reliable sources" — Hunt told associates after the Watergate break-in that he was ordered to kill the columnist in December 1971 or January 1972. The plan allegedly involved the use of poison obtained from a CIA physician. The Post reported that the assassination order came from a "senior official in the Nixon White House," and that it was "canceled at the last minute . . . "

In an affidavit about a key meeting on the matter with his White House boss, Hunt said Charles Colson "seemed more than usually agitated, and I formed the impression that he had just come from a meeting with President Nixon."

Liddy admitted that he and Hunt had "examined all the alternatives and very quickly came to the conclusion the only way you're going to be able to stop (Anderson) is to kill him . . . And that was the recommendation." Shortly after the Watergate break-in in 1972, Liddy offered to be assassinated himself, if that would help the cover-up. He told White House counsel John Dean: "This is my fault … And if somebody wants to shoot me on a street corner, I'm prepared to have that done." In a 1980 legal case, Liddy testified that there even came a time during the Nixon presidency "when I felt I might well receive" instructions to kill E. Howard Hunt — adding, "I was prepared, should I receive those orders, to carry them out immediately."

An ends-justify-the-means operator, Richard Nixon ran a pro-Mafia administration that carried out an ambitious criminal agenda of its own — one that even countenanced murder. Wouldn't his Mob connections have at least provided Nixon with inside dope —if not advance knowledge — about the murder of his archrival? Is that why Nixon — a major beneficiary of President Kennedy's assassination — concealed his knowledge of what really happened in Dallas on that tragic November day 40 years ago? Is that why, as president, he turned down a new JFK assassination inquiry — even while secretly dismissing the Warren Report as a fraud? After all, it was not in Nixon's best interests — nor in those of his chief patrons, Jimmy Hoffa and the Mob — to have the public learn the truth.

If President Nixon knew that the government's official 1964 conclusions about John F. Kennedy's murder were faked, didn't he at least have the responsibility to set the record straight? Did his failure to do so make him placidly complicit in that crime too?

Watergate may not have been Nixon's biggest cover-up after all.

A Timeline of Nixon's Ties to the Kennedy Assassination

Nov. 1946: Nixon wins a House seat with financial help from Meyer Lansky and other Mob leaders. Nixon's campaign manager, Murray Chotnier, has top Mafia figures as legal clients—as well as ties to New Orleans Mafia chief Carlos Marcello and Mob-connected Teamsters official James Hoffa.

1947: Congressman Nixon intervenes to get Jack Ruby excused from testifying before a congressional committee investigating the Mafia, according to an FBI memo discovered in the 1970s.

1947: Nixon strongly backs legislation establishing the Central Intelligence Agency. Around this time, Nixon meets CIA agent E. Howard Hunt.

1950: The Senate Kefauver committee staff learns that Ruby was "a syndicate lieutenant who had been sent to Dallas to serve as a liaison for Chicago mobsters," a former committee staffer later discloses.

Nov. 1950: Nixon is elected to the Senate from California after suggesting his opponent was a communist sympathizer.

Nov. 1952: As Dwight Eisenhower's running mate, Senator Nixon is elected vice president— despite a scandal over a secret slush fund put together by wealthy California backers.

Nov. 1956: Eisenhower is re-elected president with Nixon as his vice president.

1959-1960: Vice President Nixon and CIA agent E. Howard Hunt are key figures in secret CIA efforts to overthrow Cuban leader Fidel Castro. Nixon reportedly is the chief mover behind an associated CIA/Mob plan to murder Castro. Hunt later admitted his role in Castro assassination plots.

Summer of 1960: The CIA asks Nixon crony Robert Maheu—a former FBI agent with Mob contacts—to find mobsters who might be able to pull off a hit on Castro.

Nov. 1960: Sen. John F. Kennedy defeats Nixon in a 1960 presidential cliff-hanger; after his January 1961 inauguration, the new president goes ahead with secret Nixon-Hunt plans for a CIA-backed invasion of Cuba.

April 1961: The amphibious invasion at the Bay of Pigs is a monumental failure; Nixon, CIA, and Cuban exile leaders blame Kennedy for withholding planned U-S air cover. Kennedy privately blames the CIA and threatens to dismantle the agency.

Nov. 1961: Kennedy fires Nixon buddy Allen Dulles as CIA chief.

Nov. 1962: Nixon is defeated for governor of California after a secret $205,000 "loan" from Mob-linked billionaire Howard Hughes to Nixon's brother becomes a major issue; Nixon soon moves to New York and becomes a corporate lawyer.

1962-63: Angered by CIA incompetence during the Bay of Pigs, Kennedy moves to limit the agency's power.

Summer of 1963: Lee Harvey Oswald and the CIA- and Mob-linked David Ferrie are seen together in Clinton, La., the House assassinations committee later learns in testimony from numerous witnesses.

July 23, 1963: Teamsters boss Jimmy Hoffa tells his lawyer, Frank Ragano, "Something has to be done. The time has come for your friend (Santos Trafficante) and Carlos (Marcello) to get rid of him, kill that son-of-a-bitch John Kennedy."

Nov. 8: Oswald allegedly writes a note to a "Mr. Hunt" asking for "information."

Nov. 21: CIA agent Hunt is spotted in Dallas at the same CIA "safe house" also visited that day by Jack Ruby and Frank Sturgis, according to testimony in a 1985 court case.

Nov. 21: Ostensibly in Dallas to attend a Pepsi Cola convention, Nixon asks the city to give President Kennedy a respectful welcome.

Nov. 21: Chicago Mob boss Sam Giancana meets with Nixon in Dallas to discuss the planned Kennedy assassination, Giancana later tells relatives.

Nov. 22: Nixon leaves Dallas, apparently before Kennedy's arrival.

Nov. 22: President Kennedy is murdered in Dallas.

Nov. 24: Ruby kills Oswald in the basement of the Dallas police jail.

1963: Nixon recommends Congressman Gerald Ford for the Warren Commission.

1964: Nixon lies to the FBI about being in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963.

1964: Ford convinces the commission to alter a key finding—making its preposterous "single bullet" assassination theory slightly more believable, documents released in 1997 show. The theory held that one of the bullets struck Kennedy in the back, came out his neck, and then somehow critically wounded Texas Governor John Connally. Ford's change placed the back wound higher in Kennedy's body.

1964: Nixon and Ford write articles in advance of Warren Commission Report endorsing its anticipated conclusion that Oswald alone was responsible for Kennedy's assassination.

Sept. 1964: The Warren Report finds that Oswald—firing from a sniper's nest on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository—was President Kennedy' sole assassin.

Nov. 1968: In a squeaker, Nixon is elected president with big support from the Teamsters union and the Mob.

1971: After a Mob payoff of at least $300,000, Nixon grants clemency to Hoffa—who had been jailed for jury tampering in 1967.

June 1971: Former CIA agent E. Howard Hunt secretly joins the Nixon White House as the president's chief spy.

May 1972: Nixon confides to two top aides that the Warren Report was "the greatest hoax that has ever been perpetuated," a White House tape released in 2002 reveals.

June 17, 1972: A group of burglars working for Nixon's re-election is caught by Washington, D.C. police while breaking into Democratic headquarters at the Watergate complex. Hunt and former FBI official G. Gordon Liddy are soon identified as the group's supervisors.

June 23, 1972: To gain CIA help in the Watergate cover-up, Nixon tries to blackmail CIA chief Richard Helms over the secrets that Hunt might blab regarding CIA's links to "the Bay of Pigs"—which top Nixon aide Bob Haldeman later reveals to be Nixon/CIA code for the JFK assassination.

Nov. 1972: In a landslide, Nixon is re-elected president with the help of a reported $1 million Teamsters' contribution.

May 1973: Haldeman reminds Nixon that he—Nixon himself—had informed him that the CIA was hiding big "Bay of Pigs" secrets—though this was not disclosed until 1996, when the National Archives released a new batch of Watergate tapes. Sections of numerous Nixon conversations dealing with "the Bay of Pigs," President Kennedy, and E. Howard Hunt are deleted for "National Security" reasons.

1973: Nixon picks Congressman Ford to succeed the disgraced Spiro Agnew as his new vice president.

August 1974: Nixon is forced to resign the presidency over the Watergate scandal.

September 1974: President Ford grants Nixon a pre-emptive pardon for all crimes he might have committed.

Richard Nixon's Secret Ties to the Mafia

by Don Fulsom

During the height of the Watergate scandal, Atty. Gen. John Mitchell's wife, Martha, sounded one of the first alarms, telling a reporter, ''Nixon is involved with the Mafia. The Mafia was involved in his election.''White House officials privately urged other reporters to treat any anti-Nixon comments by Martha as the ravings of a drunken crackpot.

Time, however, has proved Mrs. Mitchell right.

Richard Nixon's earliest campaign manager and political advisor was Murray Chotiner, a chubby lawyer who specialized in defending members of the Mafia and who enjoyed dressing like them too, in a wardrobe highlighted by monogrammed white-on-white dress shirts and silk ties with jeweled stickpins. The monograms said MMC, because – perhaps to seem more impressive – he billed himself as Murray M. Chotiner, though, in reality, he lacked a middle name.

In this cigar chomping, wheeler-dealer, Nixon had found what future Nixon aide Len Garment called ''his Machiavelli – a hardheaded exponent of the campaign philosophy that politics is war.''

When Nixon went on to the White House, both as vice president, and later as president, he took Chotiner with him as a key behind-the-scenes advisor – and for good reason. By the time he became president in 1969, thanks in large part to Murray Chotiner's contacts with such shady figures as Mafia-connected labor leader Jimmy Hoffa, New Orleans Mafia boss Carlos Marcello, and Los Angeles gangster Mickey Cohen, Richard Nixon had been on the giving and receiving end of major underworld favors for more than two decades.

In his first political foray – a successful 1946 race for Congress as a strong anti-Communist from southern California – Nixon received a $5,000 contribution from Cohen plus free office space for a ''Nixon for Congress'' headquarters in one of Mickey Cohen's buildings.

And there was more to come.

In 1950, at Chotiner's request, Cohen set up a fund-raising dinner for Nixon at the Knickerbocker Hotel in Los Angeles. The affair took in $75,000 to help Nixon go on and defeat Sen. Helen Gahagan Douglas, whom he had portrayed as a Communist sympathizer – ''pink right down to her underwear.''

''Everyone from around here that was on the pad naturally had to go,'' Cohen himself later recalled, looking back on the Knickerbocker dinner, ''… It was all gamblers from Vegas, all gambling money. There wasn't a legitimate person in the room.'' The mobster said Nixon addressed the dinner after Cohen told the crowd the exits would be closed until the whole $75,000 quota was met. They were. And it was.

Cohen has said his support of Nixon was ordered by ''the proper persons from back East,'' meaning the founders of the national Syndicate, Frank Costello and Meyer Lansky. Why would Meyer Lansky become a big fan of Richard Nixon? Senate crime investigator Walter Sheridan offered this opinion: ''If you were Meyer, who would you invest your money in? Some politician named Clams Linguini? Or a nice Protestant boy from Whittier, California?''

Lansky was considered the Mafia's financial genius. Known as ''The Little Man'' because he was barely five feet tall, Lansky developed Cuba for the Mob during the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, when Havana was ''The Latin Las Vegas.'' Under its tall, swaying palms, gambling, prostitution and drug trafficking netted the U.S. Syndicate more than $100-million-a-year – even after handsome payoffs to Batista.

In the mid-‘50s, Batista designated Lansky the unofficial czar of gambling in Havana. This was so Batista could stop some Mob-run casinos from using doctored games of chance to cheat tourists. A shrewd, master manipulator whose specialty was gambling, Lansky was also known among mobsters as honest. It wasn't necessary to rig the gambling tables to make boatloads of bucks. Lansky directed all casino operators to ''clean up, or get out.''

Lansky, in turn, was very generous with the Cuban dictator. As former Lansky associate Joseph Varon has said: ''I know every time Myer went to Cuba he would bring a briefcase with at least $100,000 (for Batista). So Batista welcomed him with open arms, and the two men really developed such an affection for each other. Batista really loved him. I guess I'd love him too if he gave me $100,000 every time I saw him.''

Lansky saw to it that his friends were generous to Batista too. In February 1955, Vice President Richard Nixon traveled to Havana to embrace Batista at the despot's lavish private palace, praise ''the competence and stability'' of his regime, award him a medal of honor, and compare him with Abraham Lincoln. Nixon hailed Batista's Cuba as a land that ''shares with us the same democratic ideals of peace, freedom and the dignity of man.''

When he returned to Washington, the vice president reported to the cabinet that Batista was ''a very remarkable man … older and wiser … desirous of doing a good job for Cuba rather than Batista … concerned about social progress…'' And Nixon reported that Batista had vowed to ''deal with the Commies.''

What Nixon omitted from his report was the Batista-Lansky connection, the rampant government corruption under Batista – and the extreme poverty of most Cubans. The American vice president also ignored Batista's suspension of constitutional guarantees, his dissolution of the country's political parties, and his use of the police and army to murder political opponents. Twenty thousand Cubans reportedly died at the hands of Batista's thugs.

Under Batista, Cuba was the decadent playground of the American elite. Havana was its sin city paradise – where you could gamble at luxurious casinos, bet the horses, play the lottery, and party with the some of best prostitutes, rum, cocaine, heroin and marijuana in the Western Hemisphere. Should you have been in the mood, you could also have watched ''an exhibition of sexual bestiality that would have shocked Caligula,'' according to Richard Reinhart in an article he wrote for American Heritage in 1995 entitled ''Cuba Libre.''

Cuba was only a one-hour flight away from the United States. And there were 80 tourist flights-a-week from Miami to Havana, at a cost of $40, round trip.

Three Syndicate gamblers from Cleveland — including Morris ''Moe'' Dalitz, a friend of Nixon's best buddy Bebe Rebozo — were part owners of Lansky's glittering Hotel Nacional in Havana. In fact, during the Batista regime, as recalled by Mafia hit man Angelo ''Gyp'' DeCarlo, ''The Mob had a piece of every joint down there. There wasn't one joint they didn't have a piece of.''

In a noteworthy reversal of that situation, the Cuban dictator owned part of at least one Mob-run gambling operation in the United States. Batista was partners with New Orleans godfather and future Nixon benefactor Carlos Marcello of a casino in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana called ''The Beverly Club.''

Another Rebozo associate, Tampa godfather Santos Trafficante, was the undisputed gambling king of Havana. Trafficante owned substantial interests in the San Souci – a nightclub and casino where fellow gangster Johnny Roselli had a management role.

The relationship between Nixon and Rebozo tightened in Cuba in the early ‘50s, according to historian Anthony Summers, when Nixon was gambling very heavily, and Bebe covered Nixon's losses – possibly as much as $50,000. Most of Nixon's gambling took place at Lansky's Hotel Nacional. Lansky rolled out the royal treatment for Nixon, who stayed in the Presidential Suite on the owner's tab.

As far back as 1951, Bebe Rebozo – the man who bailed out Nixon at the Nacional – had been involved with Lansky in illegal gambling rackets in parts of Miami, Hallandale, and Ft. Lauderdale, Fla. Former crime investigator Jack Clarke recently disclosed those operations, adding that Rebozo was pointed out to him, back then, as ''one of Lansky's people …When I checked the name with the Miami police, they said he was an entrepreneur and a gambler and that he was very close to Meyer.''

A bachelor, Rebozo was short, swarthy, well dressed and ingratiatingly glib. The American-born Cuban had risen from airline steward to wealthy Florida banker and land speculator.

Many Nixon biographers say Richard Danner, a former FBI agent gone bad, introduced Nixon to Rebozo in 1951. Danner was the city manager of Miami Beach when it was controlled by the Mob. Danner eventually became a top aide to Nixon's financial angel, eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes. And, years later, during the final act of the Watergate scandal, Danner delivered a $100,000 under-the–table donation from Hughes to President Nixon.

Nixon and Rebozo hit it off almost immediately. Their mutual friend, Sen. George Smathers of Florida, once said: ''I don't want to say that Bebe's level of liking Nixon increased as Nixon's (political) position increased, but it had a lot to do with it.''

The two men were almost inseparable from then on. Rebozo was there to lend moral as well as financial support to his idol through Nixon's many political ups and downs. He was there in Florida in 1952 when Nixon celebrated his election to the vice presidency; Rebozo was in Los Angeles in 1960 when Nixon got word that Sen. John Kennedy had edged him out for the presidency; he comforted Nixon after his 1962 defeat for California governor; and Rebozo and Nixon drank and sunbathed together in Key Biscayne after Nixon's political dreams came true and he won the 1968 presidential election. During Nixon's White House years, rough estimates show Rebozo was at Nixon's side one out of every 10 days.

Known as ''Uncle Bebe'' to Nixon's two children, Trisha and Julie, Rebozo frequently bought the girls – and Nixon's wife Pat – expensive gifts. He purchased a house in the suburbs for Julie after she married David Eisenhower. The Saturday Evening Post, in a March 1987 article, put the price at $137,000.

Rebozo came in and out of the White House as he pleased, without being logged in by the Secret Service. Though he had no government job, Rebozo had his own private office and phone number in the executive mansion. When he travelled on Air Force One, which was frequently, Bebe donned a blue flight jacket bearing the Presidential Seal and his name. (Nixon's own flight jacket was inscribed ''The President'' – as though no one would recognize that fact by just looking at him.)

Rebozo's organized crime connections were solid. For one, he had both legal and financial ties with ''Big Al'' Polizzi, a Cleveland gangster and drug kingpin. Rebozo built an elaborate shopping center in Miami, to be leased to members of the rightwing Cuban exile community, and he let out the contracting bid to Big Al, a convicted black marketer described by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics as ''one of the most influential members of the underworld in the United States.''

Nixon and Rebozo bought Florida lots on upscale Key Biscayne, getting bargain rates from Donald Berg, a Mafia-connected Rebozo business partner. The Secret Service eventually advised Nixon to stop associating with Berg. The lender for one of Nixon's properties was Arthur Desser, who consorted with both Teamsters President Jimmy Hoffa and mobster Meyer Lansky.

Nixon and Rebozo were friends of James Crosby, the chairman of a firm repeatedly linked to top mobsters, and Rebozo's Key Biscayne Bank was a suspected pipeline for Mob money skimmed from Crosby's casino in the Bahamas. By the 1960s, FBI agents keeping track of the Mafia had identified Nixon's Cuban-American pal as a ''non-member associate of organized crime figures.''

Former Mafia consigliere Bill Bonanno, the son of legendary New York godfather Joe Bonanno, asserts that Nixon ''would never have gotten anywhere'' without his old Mob allegiances. And he reports that — through Rebozo — Nixon ''did business for years with people in (Florida Mafia boss Santos) Trafficante's Family, profiting from real estate deals, arranging for casino licensing, covert funding for anti-Castro activities, and so forth.''

If friendships enabled Nixon to craft links with the Mafia, so did hatred. Teamsters union leader Jimmy Hoffa hated John and Robert Kennedy as much as Nixon did. Robert Kennedy had been trying to put Hoffa in jail since 1956, when RFK was staff counsel for a Senate probe into the Mob's influence on the labor movement. In a 1960 book, Robert Kennedy said, ''No group better fits the prototype of the old Al Capone syndicate than Jimmy Hoffa and some of his lieutenants.''

Because he shared a common enemy with Nixon, Hoffa and his two million-member union backed Vice President Nixon against Sen. John Kennedy in the 1960 election, and did so with more than just a get-out-the-vote campaign. Edward Partin, a Louisiana Teamster official and later government informant, revealed that Hoffa met with New Orleans godfather Carlos Marcello to secretly fund the Nixon campaign. Partin told Mob expert Dan Moldea: ''I was right there, listening to the conversation. Marcello had a suitcase filled with $500,000 cash which was going to Nixon ... (Another $500,000 contribution) was coming from Mob boys in New Jersey and Florida.'' Hoffa himself served as Nixon's bagman.

The Hoffa-Marcello meeting took place in New Orleans on Sept. 26, 1960, and has been verified by William Sullivan, a former top FBI official.

Nixon lost the 1960 election, and Hoffa – thanks to Atty. Gen. Robert Kennedy – soon wound up in prison for jury tampering and looting the union's pension funds of almost $2 million. But the Nixon-Hoffa connection was strong enough to last at least until Dec. 23, 1971 when, as president, Nixon gave Hoffa an executive grant of clemency and sprung him from prison. The action allowed Hoffa to serve just five years of a 13-year sentence.

Hoffa evidently bought his way out. In 1996, Teamsters expert William Bastone disclosed that James P. (''Junior'') Hoffa and racketeer Allen Dorfman ''delivered $300,000 ''in a black valise'' to a Washington hotel to help secure the release of Hoffa's father'' from the pen. The name of the bagman on the receiving end of the transaction is redacted from legal documents filed in a court case. Bastone said the claim is based on ''FBI reports reflecting contacts with (former Teamster boss Jackie) Presser in 1971.''

In a recently released FBI memo confirming this, an informant details a $300,000 Mob payoff to the Nixon White House ''to guarantee the release of Jimmy Hoffa from the Federal penitentiary.''

Breaking from clemency custom, Nixon did not consult the judge who had sentenced Hoffa. Nor did he pay any mind to the U.S. Parole Board, which had unanimously voted three times in two years to reject Hoffa's appeals for release. The board had been warned by the Justice Department that Hoffa was Mob-connected. Long-time Nixon operative Chotiner eventually admitted interceding to get Hoffa paroled. ''I did it,'' he told columnist Jack Anderson in 1973, ''I make no apologies for it. And frankly I'm proud of it.''

At the time, The New York Times called the clemency a ''pivotal element in the strange love affair between the (Nixon) administration and the two-million-member truck union, ousted from the rest of the labor movement in 1957 for racketeer domination.''

As one example of President Nixon's ''strange love affair'' with the Teamsters, in a May 5, 1971 Oval Office conversation, Nixon and his chief of staff Bob Haldeman pondered a little favor they knew the union would be happy to carry out against anti-war demonstrators:

Haldeman: What (Nixon aide Charles) Colson's gonna do on it, and I suggested he do, and I think they can get a, away with this . . . do it with the Teamsters. Just ask them to dig up those, their eight thugs.

President: Yeah.

Haldeman: Just call, call, uh, what's his name.

President: Fitzsimmons.

Haldeman: Is trying to get, play our game anyway. Is just, just tell Fitzsimmons...

President: They, they've got guys who'll go in and knock their heads off.

Haldeman: Sure. Murderers!

Veteran Mafia bigwig Bill Bonanno describes Nixon's clemency for Hoffa as ''a gesture, if ever there was one, of the national power (the Mob) once enjoyed.''

President Nixon did put one restriction on Hoffa's freedom: Hoffa could never again, directly or indirectly, manage any union. This decision, too, was the result of a financial incentive – from another wing of the Mafia. The restriction was reputedly bought by a $500,000 contribution to the Nixon campaign by New Jersey Teamster leader Anthony Provenzano –''Tony Pro'' – the head of the notorious Provenzano family, which, a House panel found in 1999, had for years dominated Teamsters New Jersey Local 560.

The Provenzanos, who were linked to the Genovese crime family, used Local 560 to carry out a full range of criminal activities, including murder, extortion, loan sharking, kickbacks, hijacking, and gambling.

During the Nixon administration, pressure from Washington eased off on other Mafia leaders, too, such as Chicago godfather Sam Giancana; long-standing deportation proceedings against CIA-connected mobster Johnny Roselli were dropped. Without going into specifics, lawyers from Nixon's Justice Department explained in court that Roselli had performed ''valuable services to the national security.''

A Giancana henchman, Roselli was an important contact man in the CIA-Mafia assassination plots against Cuban leader Fidel Castro. (Roselli and Dallas gangster Jack Ruby – the killer of JFK assassination suspect Lee Harvey Oswald – are reported to have met in hotels in Miami during the months before the JFK assassination.)

Roselli was also apparently acquainted with longtime Nixon associate CIA agent E. Howard Hunt. Nixon and Hunt were secretly top planners of the assassination plots on Castro when Nixon was vice president. And later, Roselli and Hunt are reported to have been co-conspirators in the 1961 assassination-by-ambush of Rafael Trujillo, dictator of the Dominican Republic. In the ‘70s, a Senate committee established that the CIA had supplied the weapons used against Trujillo. In 1976, Cygne, a Paris publication, quoted former Trujillo bodyguard L. Gonzales-Mata as saying that Roselli and Hunt arrived in the Dominican Republic in March 1971 to assist in plots against Trujillo.

Gonzalez-Mata described Hunt as ''a specialist'' with the CIA and Roselli as ''a friend of Batista'' who was operating on orders from both the CIA and the Mafia.

Mafia Trials

The Nixon administration intervened on the side of Mafia figures in at least 20 trials, mostly for the ostensible purpose of protecting CIA ''sources and methods.''

Nixon even went so far as to order the Justice Department to halt using the words ''Mafia'' and ''Cosa Nostra'' to describe organized crime. The President was roundly applauded when he boasted about his order at a private 1971 Oval Office meeting with some 40 members of the Supreme Council of the Sons of Italy. The group's Supreme Venerable, Americo Cortese, thanked Nixon for his moral leadership, declaring, ''You are our terrestrial god.''

As president, Nixon also pardoned Angelo ''Gyp'' DeCarlo, described by the FBI as a ''methodical gangland executioner.'' Supposedly terminally ill, DeCarlo was freed after serving less than two years of a 12-year sentence for extortion. Soon afterward, Newsweek reported the mobster was not too ill to be ''back at his old rackets, boasting that his connections with (singer Frank) Sinatra freed him.''

Sinatra had been ousted from JFK's social circle when the Kennedy Justice Department reported to the President that the singer had wide-ranging dealings and friendships with major mobsters. But the Nixon White House disregarded similar reports, and Sinatra went on to become fast friends with both Nixon and his corrupt vice president, Spiro Agnew.

In April 1973, at Nixon's request, Sinatra came out of retirement to sing at a White House state dinner for Italian President Giulio Andreotti. On the night of the dinner, the president compared Sinatra to the Washington Monument – ''The Top.''

In the summer of 1973, The New York Times reported that Nixon pardoned DeCarlo as a result of Sinatra's intervention with Agnew. The newspaper said the details were worked out by Agnew aide Peter Malatesta and Nixon counsel John Dean. The release reportedly followed an ''unrecorded contribution'' of $100,000 in cash and another contribution of $50,000 forwarded by Sinatra by to an unnamed Nixon campaign official.

FBI files released after Sinatra's 1998 death seem to confirm this and provide fresh details. An internal bureau memo of May 24, 1973, describes Sinatra as ''a close friend of Angelo DeCarlo of long standing.'' It says that in April 1972, DeCarlo asked singer Frankie Valli of ''My Eyes Adored You'' and ''Big Girls Don't Cry'' fame (when Valli was performing at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary) to contact Sinatra and have him intercede with Agnew for DeCarlo's release.

Eventually, the memo continues, Sinatra ''allegedly turned over $100,000 cash to (Nixon campaign finance chairman) Maurice Stans as an unrecorded contribution.'' Vice presidential aide Peter Maletesta ''allegedly contacted former Presidential Counsel John Dean and got him to make the necessary arrangements to forward the request (for a presidential pardon) to the Justice Department.'' Sinatra is said to have then made a $50,000 contribution to the president's campaign fund. And, the memo reports, ''DeCarlo's release followed.''

Frank Sinatra's Mob ties go back at least as far as Nixon's. In 1947, the singer was photographed with Lucky Luciano and other mobsters in Cuba. The photo led syndicated columnist Robert Ruark to write three columns about Sinatra and the Mafia. The first was titled ''Shame Sinatra.''

The Nixon administration's generosity toward top Mob and Teamsters officials was truly remarkable: To cite just a few other examples:

- A few months after trouncing Sen. George McGovern in 1972, Nixon secretly entertained Teamsters chief Frank Fitzsimmons in a private room at the White House. Atty. Gen. Richard Kleindienst was summoned to the session ''and ordered by Nixon to review all the Teamsters investigations at the Justice Department and to make certain that Fitzsimmons and his cronies weren't hurt by the probes.''

- In April 1973, The New York Times disclosed that FBI wiretaps had uncovered a massive scheme to establish a national health plan for the Teamsters – with pension fund members and top mobsters playing crucial roles … and getting lucrative kickbacks. Yet Kleindienst rejected the FBI's plan to continue taps related to the scheme. The chief schemers behind the proposed rip-off had included Fitzsimmons and Teamsters pension fund consultant Allen ''Red'' Dorfman.

- From 1969 through 1973, more than one-half of the Justice Department's 1,600 indictments in organized crime cases were tossed out because of ''improper procedures'' followed by Atty. Gen. John Mitchell in obtaining court-approved authorization for wiretaps.

- During Nixon's administration, the Treasury Department declared a moratorium on $1.3-million in back taxes owed by former Teamsters president Dave Beck.

- In May 1973, the Oakland Tribune reported that Nixon aide Murray Chotiner had interceded in a federal probe of Teamsters involvement in a major Beverly Hills real estate scandal. As a result, the investigation ended with the indictment of only three men. One of the three — Leonard Bursten — a former director of the shady Miami National Bank, and a close friend of Jimmy Hoffa, had his 15-year prison sentence reduced to probation.

- In June 1973, ex-Nixon aide John Dean revealed to the Senate Watergate Committee that Cal Kovens, a leading Florida Teamsters official, had won an early release from federal prison in 1972 through the efforts of Nixon aide Charles Colson, Bebe Rebozo, and former Florida Sen. George Smathers. Shortly after his release, Kovens contributed $50,000 to Nixon's re-election effort.

By contrast, the Kennedy administration's war on organized crime was highly effective: indictments against mobsters rose from zero to 683; and the number of defendants convicted went from zero to 619.

There's evidence Nixon later made an effort to cash in on the ''good deeds'' he had performed for his Mafia friends. Records reveal that FBI agents suspected the Nixon White House of soliciting $1 million from the Teamsters to pay hush money to the Watergate burglars.

In fact, in early 1973 – when the Watergate cover-up was coming apart at the seams – aide John Dean told the president that $1 million might be needed to keep the burglary team silent. Nixon responded, ''We could get that … you could get a million dollars. You could get it in cash, I know where it could be gotten.''

When Dean observed that money laundering ''is the type of thing Mafia people can do,'' Nixon calmly answered: ''Maybe it takes a gang to do that.''

It is suspected that most of the Watergate ''hush money'' distributed to E. Howard Hunt – who, during Watergate, was Nixon's secret chief spy – and other members of the burglary team came from Rebozo and other shadowy Nixon pals like Tony Provenzano, Jimmy Hoffa, Howard Hughes, Carlos Marcello, Santos Trafficante, Meyer Lansky, and Lansky buddy John Alessio.

An ex-con, Alessio, the gambling king of San Diego, was one of the few guests at Nixon's New York hotel suite on election night, 1968. Alessio was rubbing elbows with Nixon and his family at a very special occasion – despite a mid-‘60s conviction for skimming millions of dollars from San Diego's racetrack revenues.

On May 20, 1972 an anxious Richard Nixon picked up the Oval Office phone and called Anthony Provenzano's top henchman, Joseph Trerotola, a key Teamsters union power broker in his own right. Perhaps the President had some laundered cash in mind to help keep the Watergate burglars quiet about their White House ties. We will never know for sure why Tony Pro's right-hand man was one of the first people Nixon called after the burglary. Scholars who try to listen to that recently released one-minute-long conversation at the National Archives will find that the tape has been totally erased. The Archives believes the tape was probably erased by mistake by Secret Service overseers of Nixon's taping system. But an Archives spokesman acknowledges that Nixon – or someone else – might possibly have tampered with the Nixon-Trerotola tape.

A short time before phoning the mobster, Nixon had an Oval Office conversation about Watergate with his chief of staff, Bob Haldeman. This is the famous tape that contains an 18 and one-half minute erasure. The president's secretary, Rose Mary Woods, publicly took the fall for the ''gap'' in the Nixon-Haldeman tape, saying she might have accidentally made the erasure. Many historians suspect the president was the Eraser-in-Chief. Back then, the strangest explanation of all came from Nixon aide Alexander Haig, who publicly blamed a ''sinister force.'' Behind closed doors, however, Haig told Watergate Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski that the tape in question had been ''screwed with.'' At first, Nixon went along with ''the secretary did it'' story. But he later blamed one of his Watergate lawyers, Fred Buzhardt – after Buzhardt's death.

After Nixon left office in August 1974 to avoid being impeached by Congress for the illegal activities he supervised and concealed during the Watergate scandal, he spent more than a year brooding in self-exile at his walled estate in San Clemente, Calif. The very first post-resignation invitation the disgraced ex-president accepted was from his Teamsters buddies. On Oct. 9, 1975, he played golf at La Costa, a Mob-owned California resort with Teamsters chief Frank Fitzsimmons and other top union officials. Among those who attended a post-golf game party for Nixon were Provenzano, Dorfman, and the union's executive secretary, Murray (''Dusty'') Miller.

Tony Pro would later die in prison, a convicted killer. A key Mob-Teamster financial coordinator, Dorfman was later murdered gangland-style. Murray ''Dusty'' Miller was the man, records show, gangster Jack Ruby had telephoned several days before Ruby murdered Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas in November 1963.

In July 1975, Jimmy Hoffa vanished in a Detroit suburb, and his body has never been found. Some federal investigators believe he was shot to death after being lured to a reconciliation meeting with Provenzano, who never showed up. On at least two occasions, Tony Pro had threatened to kill Hoffa and kidnap his children. Investigators theorize Hoffa's body was then taken away by truck, stuffed into a fifty-gallon drum, then crushed and smelted.

Why does the Mafia sometimes dispose of the body of a hit victim? For one thing, if there's no corpse, it's harder to find and convict the killer or killers. For another, as Robert Kennedy Mob-fighter Ronald Goldfarb observes, disposal occurs when the Mob ''wants to add shame and disgrace to a murder by embarrassing the victim's family who are left with no body or funeral, no final end.''

Jimmy Hoffa was declared legally dead in 1982.

Newly released FBI documents show that, in 1978, federal investigators sought to force former President Nixon and Teamster boss Fitzsimmons to testify about events surrounding Hoffa's disappearance. The investigators concluded that such testimony offered the last, best chance of solving the Hoffa mystery. But they accused top Justice Department officials of derailing their efforts to call the two men before a Detroit grand jury.

The records also reveal that FBI agents suspected the Nixon White House of soliciting $1 million from the Teamsters to keep the Watergate burglars silent.

The disclosures are detailed in more than 2,000 pages of previously secret FBI documents — obtained by the Detroit Free Press through a Freedom of Information lawsuit. They show that Fitzsimmons had actually been a government informant on an unspecified matter from 1972 to 1974. Could Fitzsimmons's cooperation in that case have persuaded the Justice Department to turn thumbs down on the grand jury idea?

The records don't say. But they do show that the Detroit FBI office sent a number of memos to Washington stressing that Nixon and Fitzsimmons could hold the answers to the Hoffa case.

Robert Stewart, a former assistant U.S. attorney in Buffalo, N.Y., who helped lead the investigation into just how Hoffa vanished, said in another memo: ''The one individual who could prove the matter beyond a doubt is Richard Nixon.'' Stewart wasn't sure whether Nixon would cooperate, given that he had been pardoned by successor Gerald Ford for his involvement in the Watergate scandal. But the investigator added that Nixon ''must certainly appreciate that while the pardon may protect him as to whatever happened in the White House, a fresh perjury committed in a current grand jury would place him in dire jeopardy.''